The original Macintosh shipped with a very simple control panel that allowed users to adjust their computer’s volume, mouse tracking speed and desktop background, among other things:

Today, System Preferences is a bloated mess compared to Susan Kare’s 1984 masterpiece:

However, the history from the original Macintosh Control Panel to Maverick’s System Preferences isn’t a linear one.

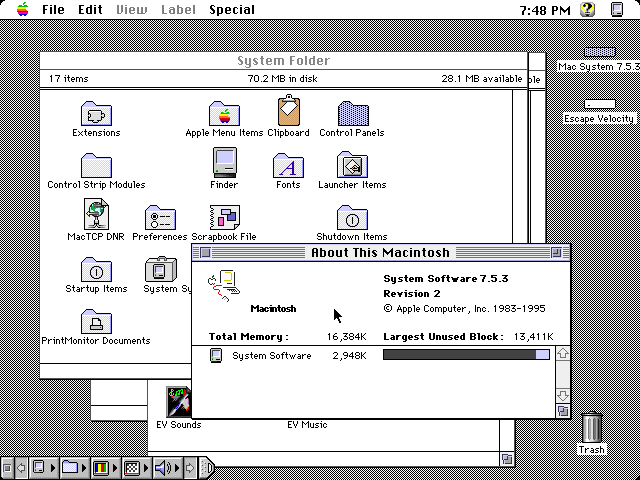

In 1994, with the System 7.1-running PowerBook 500 series of notebooks and the Duo 280c,[1] Apple introduced the Control Strip, which can be seen in the lower left of this screenshot:

(For you pedantic readers, yes, my screenshot is of 7.5.3., but as that’s the first version of the Mac’s system software to ship with the Control Strip enabled for all models of Mac.)

The Control Strip took commonly-changed settings and made them more accessible by putting them on the screen at all times. The entire strip could be collapsed or opened up with a hot key and could be moved fairly easily via the Control Strip Control Panel.

(Really.)

With System 7, the Control Strip was fairly simple, but over time it grew. By the time Mac OS 9 rolled around, these were the default Control Strip tiles Apple was shipping:

- AirPort

- AppleTalk

- Battery Monitor

- CDStrip (worked as a miniature audio CD player)

- Energy Settings

- File Sharing

- Keychain

- Location Manager

- Media Bay (for owners of PowerBook G3s with dual docking bays)

- Monitor BitDepth (to adjust color settings)

- Monitor Resolution

- Printer Selector

- Remote Access

- Sound Volume

- SoundSource (for use when recording audio)

- Speakable Items

- TV Mirroring (supported by some Power Macintosh models)

- Video Mirroring

- Web Sharing

Additionally, users could add their own Control Strip tiles, customizing the tool to meet their specific needs.

Many of these Control Strip tiles were representatives of Control Panels buried deeper in the system. A user could put their Mac to sleep or change between “Better Conservation” and “Better Performance” settings on a PowerBook using the Energy Saving tile, but fine-tuning sleep settings required a trip to a Control Panel. Likewise, the AppleTalk tile could make simple adjustments, but dealing with anything complex was out of the Control Strip’s reach.

That’s a situation that should sound familiar, as it’s how Apple’s menu bar applications work today.

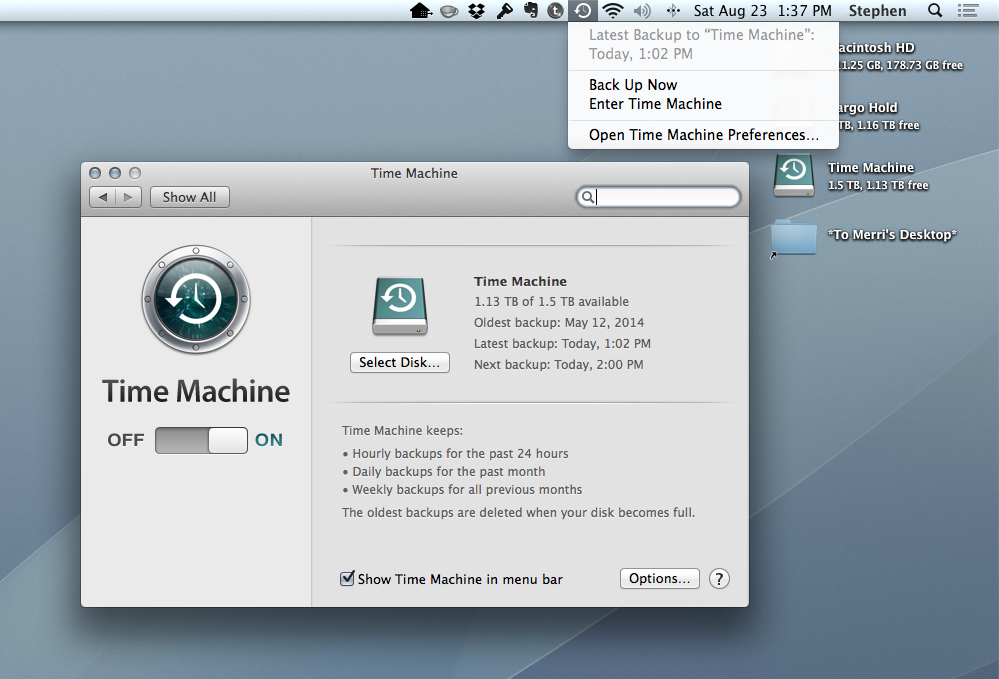

Let’s take Time Machine as an example. Its menu bar application is really just a list of shortcuts, which are helpful, but any setting changes must be done within Time Machine’s preference pane:

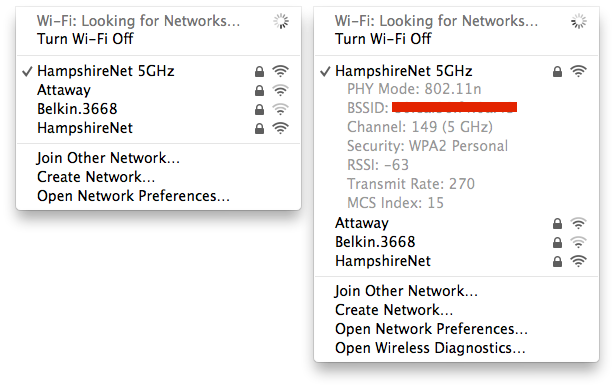

Some of Apple’s menu bar applications have tricks up their sleeves, like the Airport menu, which shows additional connectivity information if invoked when the Option key is held:

For the most part, the spirit of System 7’s Control Strip is still very much alive on the Mac. While OS X’s menu bar can become crowded with third-party utilities that do all sorts of crazy things, Cupertino is continuing to do what it’s done for two decades in this corner of their desktop OS.

- The PowerBook Duos are cool machines for lots of reasons, not the least of which is their range of Apple-made docking stations. ↩