In the Brushed Metal Diaries, we take a look at one of Apple’s most unique — and most hated — user interface paradigms.

In our modern, always-on world, finding just about anything online is just a Google search away, that hasn’t always been the case. Today we’re looking at an old app that brought the Internet to Mac users the world over.

Sherlock 1

In October 1998, Apple shipped Mac OS 8.5. The first PowerPC-only release of the Mac OS came with a much simpler installer, an improved Help system and Sherlock:

The OS 8.5 promo artwork featured Sherlock heavily, showing just how important the software was to the release.

Here’s how Apple introduced the application:

The Find File application, previously located in the Apple menu, has been expanded and renamed Sherlock in Mac OS 8.5. It includes two additional features: Find By Content and Search Internet. In addition, Sherlock allows you to save search settings into a settings file which can be used to quickly perform searches.

Sherlock looked like a regular OS 8 application but packed a punch. Its tabbed interface allowed users to find items on their disk or mounted volumes, find items based on content (think Spotlight’s ability to see inside documents) and find things on the Internet.

That last one was a big deal:

Sherlock wasn’t really searching the actual Internet in some cases. Here’s Apple again:

Internet search site files may be periodically updated for changes in search engines or to take advantage of newer features. When performing an Internet search with a search source file, an automatic check is performed to determine if an updated search source is available.

For 1998, this was forward-thinking — Google was founded just one month before Mac OS 8.5 shipped — and it was clear that Apple was thinking about the Internet. In tandem with the iMac G3, the company was making a bet that the Internet was going to be a critical component to the future of Apple’s products.

Sherlock 2

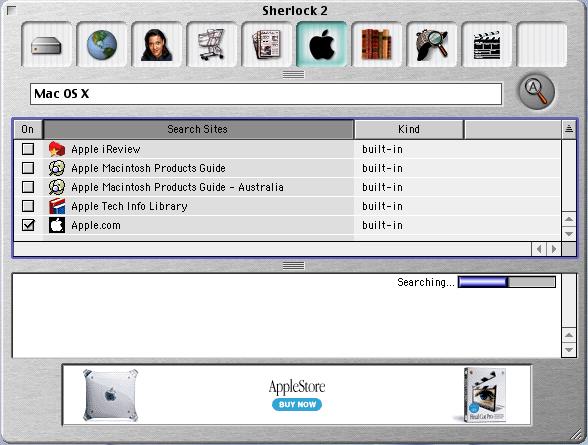

Shipping with Mac OS 9 a year later in October 1999, Sherlock 2 was a major step forward for the application.

It also came dressed up like our old friend, QuickTime 4:

Sherlock 2 was a stand-alone application. Instead of the tabbed interface that was used in OS 8.5 and 8.6, this version of the application had various channels. In addition to file search, the application could find content on the open Internet, contact information, news, Apple news, entertainment and more. In addition to this better organization method, Sherlock 2 auto-updated its search site database.

A Brief — but Necessary Sidebar — on Watson

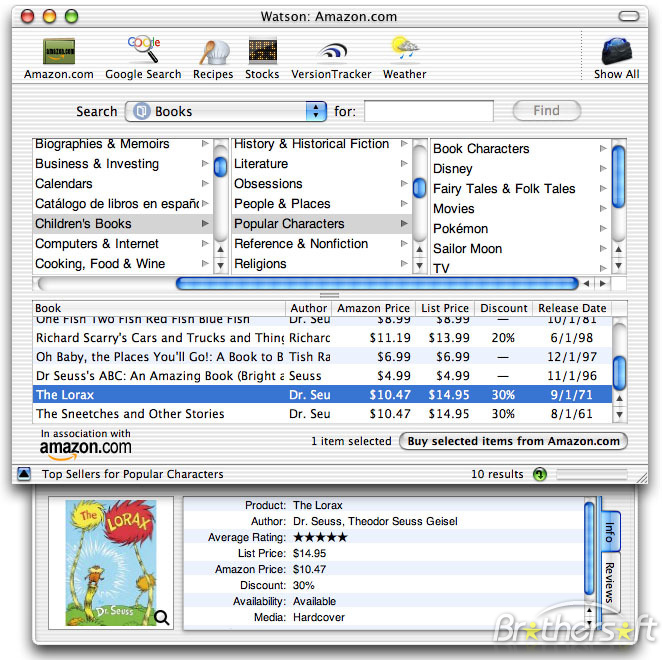

Many Apple fans will recognize the term “sherlocking.” It comes from the drama sorrowing an application named Watson.

Built by developers at Karelia Software, Watson shipped in November 2001 as an Internet search application for Mac users. Taking advantage of OS X-only technology, Watson won many awards — including an Apple Design Award.

Of course, the devil’s advocates among Apple fans said that Karelia Software designed Watson to infringe on what Apple was doing with Sherlock. The application shipped with an interface that looked like Sherlock, and of course, a name that was probably too similar to Apple’s.

In 2004, Watson was sold to Sun Microsystems. The company announced that it was going to port the application to Java, but not much ever happened with that effort.

In short, Apple copied Watson with later Sherlock versions and killed the third-party app in the process, and a term that remains in the industry remains alive and well today.

Sherlock 3

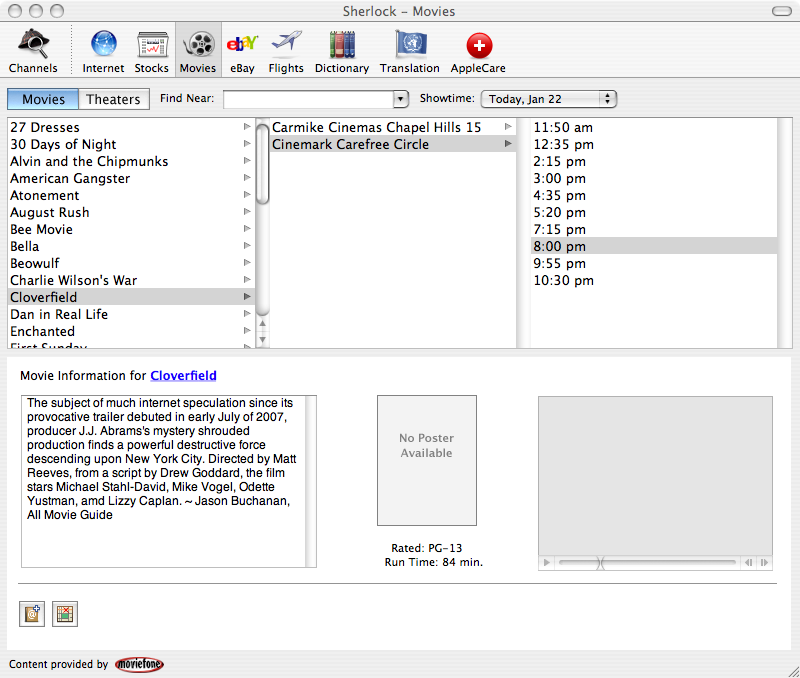

Watson was a big deal because of Sherlock 3, which shipped with Mac OS X 10.2. The new app dropped local search, becoming an Internet-focused application. In addition to the previous channels, Sherlock 3 could find data from online services, including databases of flight data, language translation and more.

In the process, Sherlock lost its brushed metal and picked up some pinstripes:

Sherlock 3, however, was short-lived. With 10.4 Tiger, Sherlock played second-fiddle to Spotlight, and the app wasn’t included with 10.5 Leopard.

Conclusions

Sherlock is a really interesting app. As it spanned several generations of Mac OS releases, each major release of the application sported a different user interface. Platinum, Brushed Metal and Pinstripe-flavored Aqua all make an appearance.

Past that, Sherlock embodied so much about the Mac and the Internet in this time frame. In the late 1990s, web portals were how people got stuff done on the Internet. Sherlock brought that idea to the desktop.

While Sherlock itself looks and feels dated in a Google-powered world, it shows that Apple hasn’t changed all that much. Just like the Apple of today, Sherlock-era Apple tried to bring the power of the Internet to rich, native apps.